What makes an artistic work great and beautiful? In Introduction to the Arts of Beauty, French philosopher Étienne Gilson invites us to reflect on the nature of art and what defines artistic work. In setting out his theory on the philosophy of art, Gilson takes the reflection on art out of the clouds and puts it into a new perspective. Art, placed in this new approach, becomes a product that springs not from a pre-conceived essence in nature or in the artist's mind, but a continuous and spontaneous product of the artist's process of doing for the sake of doing.

Tiago Barreira

What is art? What makes an artistic work great and beautiful? There are two possible ways of answering this question. The first is the classical and Platonic approach, which defines beautiful art as the manifestation of a timeless and universal ideal of Beauty, transcendent of individuality, culture and history. This group includes conservative thinkers such as Roger Scruton. The second is the modern approach, which sees art as a product of the inner affirmation and artistic subjectivity of the genius of an individual, people or culture, which is changeable and does not obey objective and external judgments of beauty. This group, present in germ in 19th century romanticism and manifested by Herder and Nietzsche, would deepen further with the advent of modernism and post-modernism in the 20th century.

There was, however, a thinker in the Christian camp in the 20th century who managed to strike a balance between the two strands, contemplating both the virtues of the formalism of classical theory and the subjectivism of modern art theory. This is what the French medievalist philosopher Étienne Gilson reveals.

In Introduction to the Arts of Beauty - What is Philosophizing about Art?Gilson invites us to reflect on the nature of art and what defines artistic work. By presenting a theory on the philosophy of art, Gilson opposes conventional theories of aesthetics centered on the search for an essential purity in art.

Art as factivity

Gilson begins his work by raising the main question about the problem of art. How can it be defined? The answer must be sought from the classification given by Aristotle to the fields of human activity. Based on Aristotelian philosophy, Gilson establishes that there are three main operations of man: knowing, acting and doing,

For Gilson, these three operations are distinguished in terms of the types of objects they address. The operations of the order of knowledge are the objects of logic, epistemology, grammar and all the sciences and arts of language and expression. The operations of the order of action constitute the object of ethics and its domain is that of morality. The operations of the order of doing, on the other hand, are related to what he calls factivityThey are linked to production and manufacturing in all its forms, and constitute a distinct order.

For Gilson, therefore, all the arts fall under the heading of factivity. There is only art where the operation consists neither in knowing nor in acting, but in "produce and manufacture".

Gilson points out that man has always been a maker of things, from the beginning. homo faberThe activity of making is a kind of promotion of their act of existence. Prehistory shows the presence of objects that cannot be considered works of nature, but human works. Gilson observes that the immense development of industrial production, especially since the invention of machines that operate like tools, attests to the strength of this primitive need to manufacture and the fruitfulness of which man is capable. For Gilson, man has therefore always possessed the spontaneous need to make something.

Gilson restores the word art to its most general meaning, i.e. that of the traditional expression of Arts & Crafts (arts and crafts), it can be said that in a broad sense the products of industry, and all the great works of man, are works of art. In this sense, every work of art produced, including those made for useful purposes, possesses some degree of beauty.

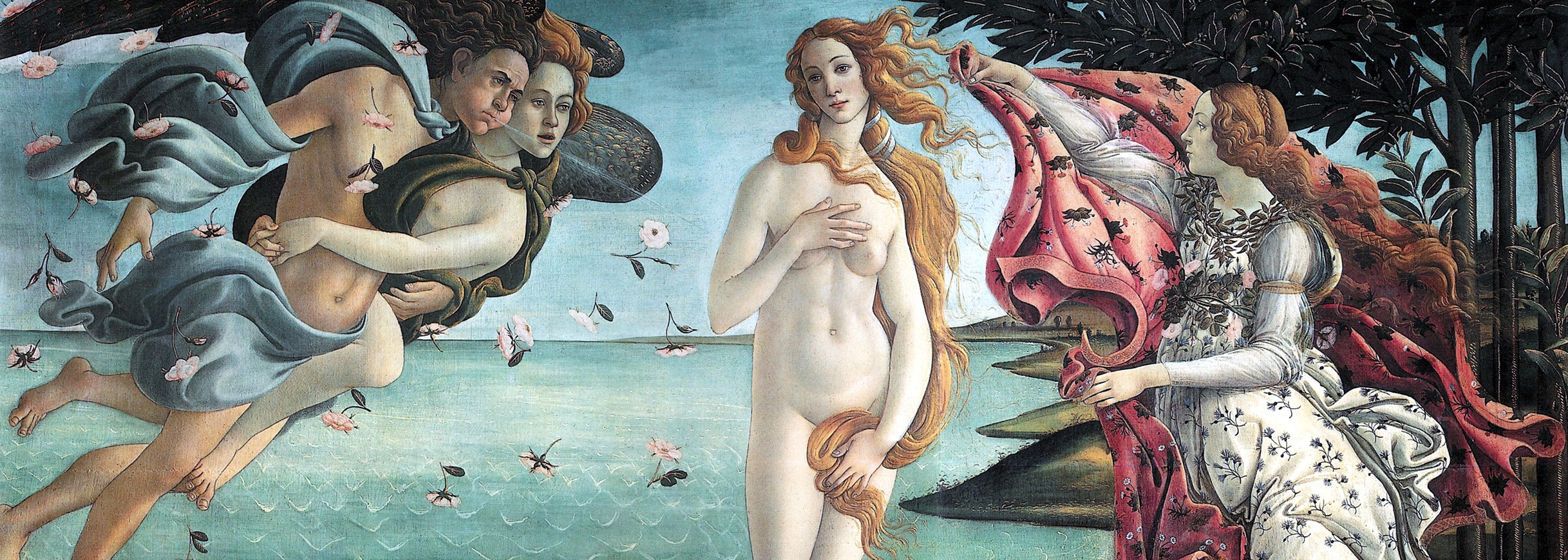

The beauty of a turbine and an automobile, Gilson continues, belongs to the beauty of man-made works, but these products of art were not made for their beauty, being a "functional" beauty. It is up to the arts of beauty - or the fine arts, such as music, poetry, literature and painting - to play this role. Therefore, to reflect on the arts of beauty is to have as our object the set of domains of factivity whose own end is to produce beautiful things, whatever their genre of beauty.

The mistake of philosophers and aesthetes

Gilson then considers that, precisely because art is fabrication, it is also work, effort, toil, technical care - things, in short, that do not stroke the heart or engender any passion. By taking these aspects into account when evaluating an artistic work, the philosophy of art ends up distinguishing itself sharply from aesthetic philosophy. Gilson points out that there needs to be a distinction "between the point of view of the artist and that of the spectator, listener or reader", and the philosophy of the arts that produce beauty should not be confused with the philosophy of the arts that produce beauty. "philosophy of the set of experiences in which we contemplate beauty".

Gilson notes that for centuries, sages, scholars and philosophers considered the life of knowledge and contemplation to be different - and higher - than practical life. Many tended to neglect the class of artists, which at the time was indistinguishable from slaves and, later, from simple manual workers. Thus, the philosopher notes:

"Contrary to this prejudice, man can do more than he knows - in this respect, he resembles nature, which produces much and knows nothing. Although man's knowledge considerably increases his power with science and knowledge, the forces that this knowledge puts at his disposal are still natural forces.“

In this sense, the artist is also similar to nature: above all, he can do much more than he knows."Were there any aesthetes in Lascaux? No doubt, but there were painters". An artist doesn't need to know what art is, as long as he knows what he wants his art to be.

Art is not imitation

Gilson then notes that philosophers of aesthetics, by ignoring the dimension of art from the point of view of the artist's doing, have ended up creating theories that do not reflect the true nature of art.

Gilson looks, for example, at the classical theory of artistic beauty. The classical definition, the philosopher continues, establishes artistic Beauty in its essence as the splendor of Truth. Developing the same principle, truth ended up being defined as "nature", and the purpose of art would be the imitation of this nature.

The doctrine of art as imitation, according to Gilson, is seen as the unfortunate root of a confusion between the beauty of knowledge and the beauty of art. Right: "Who cares about the truth or falsity of what a poem, a novel, a tragedy, a drawing or a painting shows us?" In fact, a work of art is neither true nor false.

Art therefore escapes the classic definition of imitation of truth and nature. For Gilson, it is the task of philosophers to combat this error, in order to seek the beauty of art in itself, and not in external things. From the outset, it is a matter of clearly seeing that the beauty of a written or painted work is due to the "its unity, integrity and perfection, but that these qualities must be of the work itself, and not of what it represents". It's the integrity of the work that counts, not the subject represented.

Art is not inspiration

Gilson continues his analysis of the aesthetic theories of art. According to him, if the classical doctrine of art as an imitation of nature is confusing, equally confusing is the romantic doctrine, which reduces art to any kind of subjective intuition and prophetic inspiration by the mind of an artist.

Romantic theory, although based on a notion of art that respects the creativity of the artist, inherits the difficulties of classical doctrine by still conceiving the value of an artistic work as a mere vehicle for a representation. In this case, instead of this representation being of things from the outside world, it is of subjective ideas from the artist's inner world, reducing art to a mirror of an inner revelation.

The doctrine of art-inspiration, therefore, like any intellectualist interpretation of art, conceives the creative fruitfulness of art as analogous to the invention of a new idea. However, are ideas really products of the human mind? Gilson believes not, stating that "the most powerful creative imagination always remains the imagination of one man", and all the images it produces, composes and imposes on matter do not originate in its mind, but have their ultimate origin in the sensations that existing objects cause us.

In other words, the greatest criticism of this romantic mentality lies in the fact that man, being contingent in time, can never bring an eternal idea into existence or foresee it, because he doesn't have full creative control over it, as divine creation would be, the work of an eternal author. Man is not the full author of his ideas, but God.

Art as production (poiesis)

So how is the artistic work created if it is not inspired by an ideal model? It creates itself through the artist's own act of making. This is what Gilson brilliantly explains in the following passage:

"Everyone carries within them the germ from which, in some cases, the power to produce works of art will later develop; the child who, learning to write, sensitively experiences in his hand the pleasure of drawing letters; the man whose fist seems to invent an initial or signature by itself; the traveler who accompanies the rhythm of the train with a song; the child who draws trees and dolls without even paying attention to those around him; the teenager who discovers the pleasure of making verses and who will perhaps become an impenitent versifier, whose all too visible conscience guarantees sincerity - what, in these cases, is the relationship between what they do and any intuition?"

For Gilson, therefore, it is in this primitive productivity of the artist that we find the principle of all the arts of beauty, as well as all the arts of utility, insofar as both have the effect of increasing reality.

Making or producing is, therefore, precisely the first element and, as it were, the very essence of poietic knowledge, defining its specificity. It is knowledge in view of the production of a work, not in view of itself or for the manifestation of a truth.

When a philosopher talks about beauty, Gilson says, it is rarely the beauty of art that he has in mind. It is rather the idea of beauty that holds his attention. The Western philosophical tradition, Gilson continues, has always remained faithful to this point of view, which reduces art to knowledge and makes the beauty produced by man a variety and "copy" of the truth intuited or imitated. They make the artist out to be a kind of "seer" when they talk about him.

Contrary to this view, Gilson sees the artistic work not as a product with a finished essence that is closed in on itself, foreseen by the artist, but as a work that is open and part of a continuous act of free self-expression by the author. Art as a process and a spontaneous reflection of life and artistic existence, and not a prefabricated, ready-made essence.

The subject doesn't matter in art

Gilson believes that because art is free, the end justifies the means. There is nothing to stop the artist from putting his art at the service of a moral, patriotic or religious cause, or even at the service of representing naturalistic themes, such as a still life. But the art he uses for these various purposes, in the "service" of these causes and themes, remains essentially foreign to all of them. Right:

"By freely choosing his end, the artist is also free to choose his means, which are completely justified if they enable him to achieve it. In art, the good is the successful. Because art consists of incorporating a form into a certain material with the aim of producing beauty. "

Take, for example, a work of modern art, so criticized by the classical aesthetes. For Gilson, modern abstract art is what contains the artistic process in its fullest form, since it is not tied to the representation of the theme or cause, expressing precisely the decision to practice an art whose beauty owes nothing to the beauty of the theme.

Christian scholasticism in modern times

For Gilson, this modern conception of art as the creative production of beautiful beings that didn't exist, rather than the representation or imitation of beings that already exist, only makes sense in a Christian worldview of creation.

The philosopher turns to scholastic thought to justify his point. It would be up to Christian theology, thanks to St. Thomas Aquinas, to find the God who can legitimately be expected to take creative initiative. According to Gilson: "Being causes beings, and, being Act, the beings it causes are also acts capable of subsisting on their own, operating and, in turn, causing beings similar to itself".

Thus, in a universe created by a primitive fecundity, everything that is acts and operates, either according to its mere nature or, like man, according to its nature and intelligence, which allows it to conceive other beings not yet realized. All the arts "They are methods to be followed in the production of works that add to those of nature that already exist, and the fine arts are therefore techniques for producing objects whose very purpose is to be beautifuls".

Taking this into account, Gilson maintains that Western man was therefore not wrong to claim his rights as a quasi-creator. To have become aware of the extent of the domain open to the artist's free initiative is therefore "a title of honor for the western man of the 19th and 20th centuries".

The limits of artistic freedom

However, Gilson also warns that conferring such a title on Western man, as we should, does not exempt us from pointing out its dangers. Existentialism and atheist humanism gain their deepest meaning here, by enthroning man as the supreme lord of reality. The aestheticization of ethics and knowledge prevails in the modern mentality, a sphere that belongs to acting and knowing, but never to doing.

Gilson believes that the only order in which man can invent the works of his will as he pleases is the arts of beauty, the domain of poietics. Alluding to Baudelaire's transgressive work, Flowers of EvilGilson goes on to say that it remains for men to cultivate this narrow domain of the art of beauty in which, precisely because it only produces "divinely useless flowers", everything is free.

In contrast, Gilson also warns of the risks of modern art extrapolating its field of action into knowledge and morality. Great artists have allowed themselves to be seduced by the spirit of modernity, sacrificing their reason and being recklessly "consumed" by their works. This should not be the path of art. If on the one hand, Gilson continues, the merit of modernity was the refusal to reduce the spirit to a mere object among objects, its greatest mistake was to encourage the reduction of all things in reality to the same spirit, "sacrificing knowledge of truth and goodness to factivity".

The solution lies, as always, in a return to wisdom, which recognizes no other primacy than that of being, "from which comes all intelligibility, all creativity, and with the beings born of its intelligent and free fecundity, the share of truth and beauty of these beings." Truth, beauty and goodness, although they operate in distinct and independent spheres of knowing, acting and doing, to be judged according to their own laws, must harmonize in the unity of the human soul in a wise way.

Conclusion

Philosophers and aesthetes have tried in vain for centuries to define what a perfect, pure, untainted art would be. The ideal "perfect" art is that which is produced within a concrete space-time, and not something that comes ready-made, planned and commissioned from a pure and abstract world of ideas.

If it's true that nothing is done without knowledge, knowledge alone doesn't do anything either. Scholastic Aristotelianism itself states that form needs to be actualized and manifested materially in concrete existence, without which it would be nothing more than an abstract possibility.

Thus, while aesthetes emphasize art in terms of its ideal and formal character, as a closed, perfect and finished product in itself, whether it is an imitation or a genius intuition of an idea, Gilson takes the reflection on art out of the clouds and puts it into a new perspective, from a material point of view. Art, placed in this new approach, becomes a product that springs not from a pre-conceived essence in nature or in the artist's mind, but a continuous and spontaneous product of the artist's process of doing for the sake of doing.

And more. As the artistic process unfolds, the essence of an artwork takes form and body through the hands of the artist. This is how great masterpieces have been created and great works of art have been conceived. Nothing very different from the art of prehistoric man. If the beauty of art is universal, its universality stems from what is most primordial in human nature, while homo faber that makes and manufactures. A doing that is as fundamental to the progress of human life and existence as the act of knowing, which has unfortunately been so neglected for centuries by theoreticians who are doctors of knowledge.

This is what Gilson rightly warns today's philosophers and scientists about: "From this world of forgotten works, as well as those he had the good fortune to see born, the philosopher lazily contented himself with enjoying them. Art owed him nothing. He died without enriching the earth with the tiniest object that would increase its beauty."

Reference

GILSON, Étienne. Introduction to the Arts of Beauty - What is philosophizing about art? São Paulo: Editora É Realizações, 2010. Trad. Érico Nogueira.

The opinions expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the institutional opinion of Ágora Perene.

Tiago Barreira is a doctoral candidate in Philosophy at the University of Santiago de Compostela (USC), a postgraduate in Philosophy at the Faculdade de São Bento-RJ, a graduate in Economics from the Fundação Getulio Vargas Rio (FGV-Rio), a consultant and data analyst. He writes regularly on topics related to economics, philosophy and culture.